Welcome to the Disney Watch-Watch, where I cover most of the Disney animated films left out of the Disney Read-Watch, starting with one of Disney’s most extraordinary works, Fantasia (1940).

Perhaps more than any other film discussed in this Read-Watch/Watch-Watch, Fantasia was a labor of pure love, a lavishly animated work of over one thousand artists, technicians and musicians. In making it, Walt Disney was determined to prove that animation could be more than just silly cartoons: it could also be high art. High art that included, not always successfully, dinosaurs, centaurs, elephant ballerinas, and terrifying demons. The result was a strange yet almost always beautiful film, arguably the studio’s greatest accomplishment, and certainly its greatest technical accomplishment until the advent of the CAPS system and computer animation in the 1990s.

It’s hard to remember now that it started off as a little Mickey Mouse cartoon.

In the years since Mickey’s major introduction in Steamboat Willie (1928), his popularity had steadily declined, a major concern for a movie studio that in the early 1930s needed the income from the cartoon shorts and Mickey merchandise. The studio had hopes that new character Donald Duck, introduced in 1934, might be a hit, but in 1936, Donald’s popularity was still in doubt. Walt and Roy Disney, looking at the amount of money devoured by Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs on a daily basis, determined that now would be a very good time to tinker with the little mouse—and hopefully regain his popularity in the process.

Animator Fred Moore was assigned the task of making Mickey more “cute” and appealing. (He would later do the same for Woody Woodpecker.) Moore accomplished this by finally giving the poor mouse white eyes with actual pupils, instead of the “scary” solid black eyes of the original, changing his face from white to a light skin tone, and adding volume to Mickey’s body. This established the main look of Mickey Mouse for the next several decades, until Disney marketers in 2007 or so noted that tourists were happily snatching up “original” Mickeys, and, with John Lasseter’s blessing, redesigned Mickey yet again to look more like the Mickey of the 1920s. The end result is that tourists can now buy all kinds of Mickey Mouses based on different time periods, plus—in select stores—Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, Mickey’s predecessor.

But in these pre-theme park, pre-internet days, Walt Disney had only one real marketing option for his new, cute Mickey Mouse: a cartoon. He wanted it to be a showstopper, and decided to make it a dialogue-free cartoon set to classical music—something he had done with mixed box office success in his earlier Silly Symphonies cartoons. He also wanted to use a major conductor, partly as a marketing ploy, partly to ensure that the music would be outstanding. Just as he was considering all of this, he met—either by complete accident (Disney legend) or by careful design (skeptical historians)—Leopold Stokowski, the conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra since 1912.

The musically eccentric Leopold Stokowski had swiftly made himself into a legend, thanks to his numerous innovations, which included a refusal to use a baton, experiments with lighting, and new, edited orchestrations of various classical pieces. Not all of these experiments met with audience, let alone critical, approval, but this sort of experimental, inventive approach was exactly what Walt Disney was looking for. Stokowski, who liked Mickey, was equally enthusiastic about directing a piece for a cartoon, and the two agreed to work together.

Characteristically, Walt Disney ended up vastly underestimating the costs for his Mickey Mouse cartoon—especially now that he was hiring several classical musicians, a theatre, and appropriate recording equipment. Equally characteristically, he responded to this not by cutting costs—a measure now needed as production costs on Pinocchio continued to soar—but by deciding to expand the Mickey cartoon into a full length feature. The cartoon did not have enough plot to be stretched into a full length movie, but he and Stokowski could, Walt Disney was convinced, find other musical pieces that could be animated.

He turned out to be correct. The final collaboration between Disney artists and Stokowski would include eight separate classical pieces, arranged and orchestrated by Stokowski, as well as introductions by critic Deems Taylor, a strange little jazz bit, an even stranger little bit with a soundtrack, and a small added cameo from Mickey Mouse.

This final collaboration is not the version most people have seen, since Disney has continually tinkered with it for various reasons since the film was released in 1940, but the most recent DVD/Blu-Ray and streaming releases, remastered again for the films 60th anniversary, are relatively close to that original. Relatively, since some frames from the Pastoral Symphony section remain buried in Disney vaults, and because the introductions are no longer voiced by Taylor, but by veteran voice actor Corey Burton (probably best known to Tor readers as the voice of Count Dooku in the Star Wars cartoons and Brainiac in various DC cartoons), since the original audio of Taylor’s voice has disintegrated past the ability of Disney engineers to reconstruct. Other sections, however, including the original, longer jazz moment, have been restored, along with the announcement of the 15 minute intermission included in the original release. The DVD/Blu-Ray release and the current streaming transfer (Netflix/Amazon) go dark for just a few seconds for the “intermission” before proceeding brightly on, presumably to prevent viewers from calling up and asking why the video/streaming has stopped for fifteen minutes, but it’s not a bad moment to hit pause and stop for a bathroom break or pop more popcorn.

I’ve seen Fantasia both ways—with the full introductions by Deems Taylor and Corey Burton, and without, and I have to say, as much as I’m generally an advocate for watching films the way they were originally meant to be presented, I think that the Taylor/Burton introductions hinder the experience of viewing Fantasia as much as they help. The problem isn’t really the voicing or Burton, a very charming man who can imitate a thousand voices with seemingly no effort, but the actual dialogue. It’s not only dull, dull, dull, but spends far too much time laboriously telling viewers what they are about to see.

In one case, the narration is even a little misleading: the introduction to the Rite of Spring sequence assures viewers that they are about to see an “accurate,” even scientific history of the Earth’s first several million years, but as many six-year-olds could tell you, the dinosaurs in that section are not exactly “accurate,” given that they include dinosaurs from vastly distinct periods, separated by millions of years of evolution. The dramatic volcanic eruptions are not necessarily all that accurate either, and showing entire mountain ranges rising and falling during a single solar eclipse—well, I suppose the moon could have gotten stuck in one place for a bit, thus causing a lot of tectonic activity, but I also don’t find this very likely.

The bigger problem, however, is that viewers aren’t really here for droning explanations about The Nutcracker Suite or Pastoral Symphony, but for the animation. In general, unless you really need that popcorn moment, my advice is to skip the introductions and the bit with the soundtrack and head straight to the animation and the music.

Most of the music, except for the Pastoral Symphony, a piece Stokowski argued against including, was selected and arranged by Leopold Stokowski, with input from Disney artists, Deems Taylor, and Disney himself—who, it seems, was also the chief genius, if that’s the word we want to use, behind the idea of trying to tie Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring to fighting and dying dinosaurs. The Pastoral Symphony was a replacement for Stokowki’s recommendation of Cydalise et le chevre-pied, which, as a ballet about fauns, in theory should have been the perfect vehicle for an animated segment featuring overly cute dancing fauns. In practice, animators had difficulty working with the piece, and decided to have the overly cute fauns dance to Beethoven instead.

If Stokowski lost control over the final music selection, he still retained responsibility for the final orchestration and scoring. He also directed the Philadelphia Orchestra in performance and during the filming of the first parts of the Toccata and Fugue, which featured live filming of the musicians in light and shadow. Recording his interpretations of the original music took seven full weeks.

His interpretations failed to win universal approval, with music critics particularly decrying the butchered versions of The Nutcracker Suite and Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony. A few critics also complained about the decision to have Schubert’s Ave Maria sung in English instead of Latin or German. Others were distressed by the decision—made by Stokowski, not Disney—to use an orchestral version of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Toccata and Fugue, originally scored, according to most scholars, for organ. The idea was not entirely new: Stokowski, who apparently had some doubts about that scoring, had created and recorded an orchestral version years before.

The loudest cries probably came from Igor Stravinsky, the one composer still alive when Fantasia was released, and who, twenty years later, would call the Rite of Spring sequence “an unresisting imbecility.” Stravinsky was annoyed to find that Stokowski had rearranged the order of the pieces, and in one section, had some instruments playing a full octave above the original. He grew even more annoyed in 1960, when Walt Disney claimed that Stravinsky had collaborated on the film and approved the storyboards and early rough drawings. Stravinsky noted that he had been in a tuberculosis sanitorium at the time and therefore had not collaborated on anything, although he admitted that he had seen—and enjoyed—an early negative of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. But even an adorable Mickey could not overcome his distress at the orchestration.

Stravinksy perhaps had a point regarding the animation as well. Rite of Spring is arguably the nadir of the animated part of the film. Partly because although the original idea was undoubtedly “dinosaurs!” the segment really doesn’t have enough dinosaurs. What it does have is a rather turgid sequence showing the origins of the earth, that manages to remain remarkably dull even with multiple eruptions, fish climbing out of water, dinosaur fights, and the said sight of dinosaurs slowly trudging off into the desert before collapsing beneath the sun and dying of thirst and turning into dinosaur skeletons. It’s depressing, is the problem. When it’s not boring, which is the other problem.

The Fantasia 2000 animators, recognizing this, went well out of their way to make their Stravinsky selection (The Firebird Suite), as bright and optimistic as possible. But in the late 1930s, Disney animators, recreating the origins of the earth, could not summon that optimism.

It’s all so depressing and dull that it’s easy to overlook, or forget, as I did until this recent rewatch, just how astonishing most of this segment is on a technical level. The special effects, in particular, are dazzling—I mean this literally, given the glittering, glowing, swirling stars and the sparks and fire that fly up in the later volcanic eruptions. Many of the frames, looked at alone, are crowded with imaginative detail—especially the underwater scenes showing life forms evolving from amoebae to fish to lumbering amphibians. It’s also one of the few early examples of animated backgrounds, something so expensive before the computer animation age that even this badly overbudget film only used animated backgrounds in a few segments here and there.

And yet, dull. Part of the problem, I think, is that too often Rite of Spring feels as if the animators are just trying to show off the effects they’ve learned to create—here! Fire! Pretty cool, right! Here, fire again!—without necessarily tying any of these effects to something meaningful or interesting. But a larger problem is that Rite of Spring is preceded by two pieces that are even more astonishing on a technical level, and a piece that’s more narratively interesting (the Mickey cartoon), and followed by a sequence which, if not exactly any of those things, is at least more brightly and creatively colored. In short, Rite of Spring, however interesting its individual frames and scenes, is surrounded by better work; taken on its own, I might like it more.

Or not. It does take forever for those dinosaurs to stagger to the desert and die.

Not that the segment that immediately follows it, the Pastoral Symphony, is a highlight either. Blending Beethoven with fauns, baby unicorns, baby flying horses, a few irritated gods, one very drunk god, some colorful centaurs and centaurettes (Disney’s word, not mine), and atrociously cute cupids who inexplicably are not destroyed by lightning bolts, the sequence often looks gorgeous, but ends up spending way way way too much time focused on the not exactly pressing concern of WILL the blue centaur manage to get laid? WILL HE? WILL HE? WELL MAYBE IF YOU WEREN’T USING ATROCIOUSLY CUTE CUPIDS AS YOUR DATING APP YOU’D HAVE A CHANCE, BLUE CENTAUR.

Like Rite of Spring, the Pastoral Symphony sequence came under heavy contemporary criticism, most notably from the Hays Commission, which thought that the centaurettes were showing entirely too many naked breasts and had to be properly covered. The naked centaurettes still bathing in the water managed to avoid censure and bikinis, but those on land donned hideous flower bras or stuck leaves on their breasts. It looks uncomfortable, itchy, and generally terrible. Animators agreed. legends claim that the entire “scandal” annoyed Disney artists so much that they deliberately chose clashing colors for the flower bras.

Meanwhile, I must note, the little cupids are all flying about completely naked. As are many of the fairies in The Nutcracker Suite and some of the doomed souls in Night on Bald Mountain. I can only assume here that the Hays Commission did not think that fairies, dead people and cupids obsessed with the romantic lives of centaurs were particularly prurient, but flirtatious centaurs with naked breasts could give people all sorts of ideas. And they’re not entirely wrong: those centaurs do give me very strong ideas about the fast forward button.

Potentially ribald thoughts were not the only problem with the centaur scenes, which, in the original, included a black centaur busily going around shining the hooves of the brightly colored, blond and red haired centaurs. Although some critics attempted to defend this by pointing to contemporary black shoe shiners—perhaps not the best excuse—Disney later chose to remove those frames and the accompanying music, which means that if you are paying close attention, yes, there is a musical jump in that scene. Two zebra centaurs with darker skin carrying wine did survive the cuts, perhaps because they aren’t the only characters carrying wine, and the centaurs do seem to make a habit of pairing up according to skin color—green, red, blue and otherwise.

One other point about this sequence stands out: the coloring. Not simply because the colors used for this piece tend to be bright and eye-popping, but because, in contrast to the previous segments, the cels and backgrounds of the Pastoral Symphony are filled with solid blocks of color. With the exception of a few scenes in Sleeping Beauty, this would become Disney’s standard coloring technique until Aladdin. It’s also the coloring technique used by Disney and Warner Bros in their cartoon shorts, giving this segment slightly more of a “cartoon” feel.

That cartoon feel persists into the next segment, the joyfully silly Dance of the Hours, which features dancing ostriches, elephants, alligators and a most elegant lady of splendid proportions, Hyacinth Hippo, modeled on the very skinny classical ballerina Tatiana Riabouchinska. Somehow or other, this all works, possibly because Hyacinth Hippo is quite aware of just how splendid she is, thank you very much.

But the major technical breakthroughs, and most memorable segments, belong to the rest of the film. The abstract Toccata and Fugue, shifting from live action shadowed filming of musicians and actors pretending to be the Philadelphia Orchestra to surreal moments of darkness and light, may not have a plot, but it does have the first examples of something new to this film—and still rare in animation today, even with computers—animated backgrounds. It also developed new effects of shimmering and light. Also, that tooth like thing lumbering down into the darkness remains a powerful image.

Animators also reached new heights in the shimmering beauty of The Nutcracker Suite, which also included a major underwater sequence developed in tandem with the underwater sequence in Pinocchio—which is also why the goldfish in Pinocchio so strongly resembles the graceful, swirling goldfish in Fantasia. But in this film, the multicolored goldfish aren’t trapped in a bowl, but allowed to dance through water, in underwater scenes that—along with the underwater scenes in Pinocchio—caused animators so many fits that they all mutually agreed to never try that again. The expenses involved cemented that decision, and Disney avoided animating underwater scenes again until The Little Mermaid.

The Nutcracker Suite, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice and the Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria sequence also feature delicate shading within animation cels, in what would be one of Disney’s last uses of that technique until the development of the CAPS system in the 1990s. Note, for example, the way that the Sorcerer’s Hat contains more than one shade of blue, or the gentle tints given to the fairies as they dance. Disney had done this before, but never with so many animated drawings.

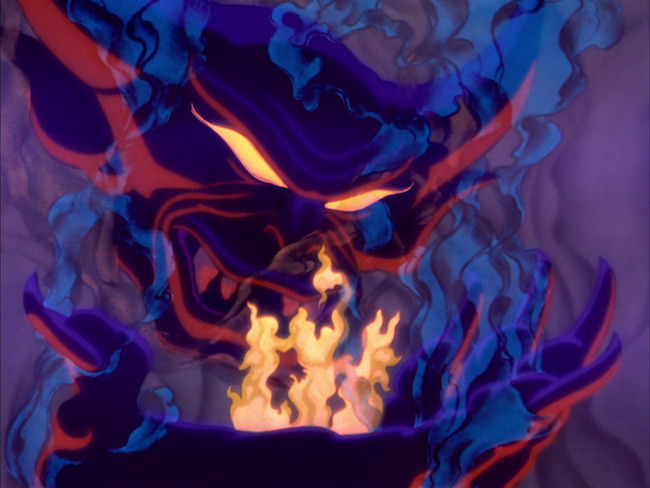

But the most memorable sequences are probably the Mickey cartoon—starring an initially gleeful Mickey, convinced he’s found an unbeatable method of getting out of work, followed by a very sad and very wet Mickey, learning far too late that chopping enchanted brooms into fragments is perhaps not the wisest idea—and Night on Bald Mountain, with its fearsome demon Chernabog summoning nearby souls to a demonic dance. This is partly because both tell fairly solid stories, but also because both contain such expressive character work. Mickey was never to be quite so engrossing again, and it would take years before Disney would create anything as convincingly malevolent as Chernabog.

The Night on Bald Mountain sequence serves another function, as well: illustrating, as it does, a figure of evil summoning souls to hell, before transitioning into a message of hope. A reflection, and perhaps an answer, to what was happening in Europe even as the artists drew, inked, and painted.

These sequences reached a level of animation that Disney was never to achieve again until the development of the CAPS system in the early 1990s, and arguably even then. And not until the wildebeest stampede in The Lion King did Disney come even close to approaching Fantasia’s sheer number of animated characters. Not counting the abstract objects in the Toccata and Fugue and the broomsticks in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, that number comes to about 500, the record for Disney hand animated films. Nor would Disney even attempt to animate backgrounds again until a few scenes in Aladdin, even in the lavish Sleeping Beauty and the pricey The Black Cauldron.

Walt Disney was so pleased with the result that he planned to make Fantasia a continually updated and released work, with sequences added and subtracted each year. Some of the concept art for additional sequences did eventually end up in the scrambled together post war anthology films, Make Mine Music and Melody Time, but otherwise, World War II put an abrupt end to that plan. The outbreak of war meant that Disney could not distribute the film in Europe, resulting in a significant loss of profits for the studio. RKO Pictures decision to release a severely edited cut of the film in most theatres also meant that viewers were seeing different versions of the film, which probably did not help. Fantasia turned into one of the most expensive losses for the studio so far, though it would be overcome later by the catastrophes of Sleeping Beauty, The Black Cauldron and Treasure Planet.

Making matters worse, most audiences could not even hear the music properly. Walt Disney had arranged for the music to be recorded in an early version of surround sound, which he called Fantasound. Unfortunately for Disney, most movie theatres did not have the funds to install the new sound system, and Fantasound was mostly a failure. Also not helping: the Fantasound recordings rapidly deteriorated to the point where Disney later found it cheaper to simply hire an orchestra to rerecord the entire score for one later release; the music and animation did not always line up precisely in that version, but at least the music could be heard.

That later release was one of many done to recoup losses on the film, a typical strategy for Disney that allowed many initially poorly performing films to eventually make a profit. Fantasia, however, was handled a bit differently. Most of the Disney films were released more or less in their original forms, with only the aspect ratios updated for modern theatres—a disaster when it came to trying to appreciate the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in the 1980s, since changing the aspect ratio meant cutting off the top and bottom of the film to give it a “widescreen” look—thus cutting off some of the animation. With Fantasia, however, Disney did not just stop at switching the aspect ratios, or in one release (in 1956) stretching some of the frames to the point of giving them a very different look. The studio added and removed bits, changed narrators, and removed frames from the original film.

None of these changes could completely destroy the art of the film. And by the 1969 release—thanks, legend has it, to the use of various not entirely legal substances—Fantasia finally became a hit, recognized as one of Disney’s major achievements.

That success also led to various attempts to restore the original film. It was not always successful, especially given the massive deterioration of the soundtrack, and issues with the film negatives, but the 2000 and the 2010 remastered versions tend to be very clean, and the 2010 version also features a seamless digital transfer that—yay—contains every frame. The original music recording has also been carefully cleaned up. If that still has too many hisses and pops for you, you now also have the option of purchasing the second music recording (directed by Irwin Kostal in 1982) from Walt Disney Records and listen to that while watching the film.

Disney followed up the belated success with its usual merchandising: plush Mickey Mouses wearing the Sorcerer’s Hat, plush Sorcerer’s Hats (I’m not going to admit to owning one, but since several people reading this have visited my house, I’m not going to deny owning one either), T-shirts and trading pins featuring various Fantasia characters (including, sigh, those centaurs). Portions of the Fantasmic! show at Hollywood Studios used images from the film, and for a few years Hollywood Studios also had a large Mickey Sorcerer’s Hat—completely blocking the view of their mock Chinese Theatre, but providing a nice shady spot to buy Stitch trading pins. It was later replaced by a stage that occasionally features dancing Stormtroopers. And eventually, Disney did get around to achieving part of Walt Disney’s dream, releasing a sequel, Fantasia 2000, which we’ll discuss in a few more posts.

It might have been an odd fit in the Disney lineup—only one film would be odder—but Fantasia still stands out as one of Disney’s most innovative and distinct works, and one of Disney’s few attempts at “art for art’s sake,” a film determined to prove that animation could be high art. And a film that at least half the time, succeeds.

That odder film is coming up in two more posts. But before we get there, Dumbo, Disney’s attempt to answer a question that up until then, had rarely been asked: just how mean can elephants get?

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

It’s worth preserving the casual racism of the past so we remember to put a mental asterisk next to it when someone starts wishing for the good old days.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Nx4ekJ0i_w

Erasure doesn’t fix racism.

I loved this film as a child. I’m fairly sure it was my first exposure to both the Nutcracker Suite and the Pastoral Symphony (well, probably my first exposure to all of it) and is probably part of what fostered my love of classical music to this day. I still can’t listen to any of those pieces without seeing the imagery.

Interestingly, as a kid, the Sorcerer’s Apprentice part was probably the dullest part to me – either that or the Dance of the Hours. It was just a bit too silly/nonsensical to me. I absolutely adored the Nutcracker Suite sequences and the Pastoral Symphony sequences (probably my budding love of fantasy) and most of the Rite of Spring (I agree that there are parts that drag a bit so sometimes that was a bathroom break for me). I actually really loved the beginning ‘evolution’ parts…funny since I ended up going into microbiology in college :)

The Toccata I liked but didn’t have many strong opinions on. And I absolutely loved the Night on Bald Mountain and all of its creepy ness (and pausing it right when the demons fly across to laugh at their having bear chests, ha). Funny fact is that it wasn’t until many years later that I realized that there was actually a whole separate segment after that – after the music started to die down and the demons retreated and the people came out with their lamps, I assumed that was the end. I didn’t realize until I was older it segues into the Ave Maria and there’s a whole animation of their procession!

The tape we still have has Deems Taylor, I think. As a kid I used to find those parts dull (although I liked the soundtrack part), along with the jazz part, but as I got older I enjoyed hearing about the music being played. Plus I just kind of liked his voice.

Excellent piece. There’s just so much that CAN be said about Fantasia and I never managed to really finish writing about it myself.

One thing that I discovered that you may find interesting is the presence of two FEMALE harpists, clearly visible in the Toccatta and Fugue piece. They are Edna Phillips and Majorie Tyre, two pioneers of women in orchestral music in the United States. At the time Fantasia was recorded, they were the only two performers in any of the “Top 5” orchestras in the country. Disney filmed all of the musicians for that number using actors– so they explicitly had to find two female actors to portray harpists– so they must have known the importance and rarity of their presence. And yet, I’ve never heard them called out in any of the DVD commentaries.

You can read my review here: http://kniggit.net/2015/09/23/disney-diary-fantasia-toccata-and-fugue-in-d-minor/

I had intended to write one post on each of the shorts, but have never finished the “Nutcracker Suite” despite doing a metric ton of research including reading both versions of the story and trying to track down original staging for the ballet DESPITE the fact that Disney doesn’t use any of the ballet’s imagery in their short. Talk about over-thinking… This is why I never get things done…

Joe

It’s fun to see how responses to the various sections of Fantasia differ. My kids at the age of about 4 and 6 thought the Dance of the Hours segment was absolutely the best thing ever.

I absolutely love this film. I find almost all of it to be incredible, including The Rite of Spring. I freely admit that’s due to the music, the technical achievement, and the fact that DINOSAURS were big in my life the first time I saw this as a kid. Night on Bald Mountain remains my favorite part of the film and I could listen to Toccata and Fugue all day. I’ve always preferred the orchestral version, anyway.

This film is definitely in my Top 100 of all time.

I didn’t catch this one till adulthood, long after discovering the music. I liked the primal earth scenes, up till the emergence on land, but not the dinosaurs’ protracted death. The oversexed centaurs were creepy, but the winged foal’s first flight was great.

Some 60 years separate the 2 films; I fear I won’t be around for the 3rd Fantasia.

As someone who was alive in 1969, I can verify that, yes, lots of drugs were taken during the watching of this film, not by me, but by many of my peers and the older Baby Boomers. It was the thing to do.

My brother and I watched this half a zillion times. We called it “the pesto movie” due to the bit where the personified “Soundtrack” turns green like pesto. Any excuse to eat the stuff.

I recognize very few pieces of classical (or otherwise lyric-less) music…except the ones I heard in Fantasia.

Rites of Spring was my favorite part and I still think it’s magnificent, despite learning more about paleontology and getting even less interested in dinosaurs compared to other lifeforms. (And I work at a paleontology museum. Does that make it a problematic fave?) Almost as scary as the horde of brooms, but much more beautiful.

I’m not generally into abstract art, but I loved Toccata and Fugue. We all may visualize different things when hearing music, but these felt about right to me.

Aaaand I loved the nature imagery in the Nutcracker Suite and the goofiness of Dance of the Hours and the combined beauty and goofiness of Pastoral Symphony. Didn’t much like the scary Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Night on Bald Mountain I watched a time or two but don’t remember well. Not sure if I ever watched Ave Maria. I think I was always pretty worn out by that point in the movie and decided to stop watching.

@1: On the debatable Cracked list of “The 9 Most Racist Disney Characters,” Sunflower was #4 and “the one Disney has tried the hardest to make us forget.” http://www.cracked.com/article_15677_the-9-most-racist-disney-characters.html (Edited to replace link)

I first saw the original Fantasia as a teenager (on a big screen; there were no VCRs yet), and it was seeing this that convinced me that you could love animation as an adult. It’s because of this that I continued watching new-release animated feature films into adulthood (with no child along as an excuse), in the decades before Pixar made that widespread. It’s also because of this that I’ve sought out animated films made for adults, such as Persepolis and The Triplets of Belleville. I have much to thank Fantasia for!

I love the seasonal imagery in Nutcracker, the silliness of the Dance of the Hours, the scary grandeur of Bald Mountain, the multiplying brooms and flooding water in the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the early evolutionary sequence in The Rite of Spring. I like some of the abstract imagery in the Bach piece, though I’m one of those who would have preferred the piece performed on the organ–a cleaner, more mathematical beauty. Like Angiportus @6, I detest the centaurs but am quite fond of the pegasi, especially the new flyer. Also, the pegasi aren’t color-segregated.

I am glad the most racist imagery has been edited out in the versions we share with children, though I agree it should be easily available for study of the history of racist imagery of American popular culture. The same goes for racist visuals in other Disney animated works, such as Santa’s Workshop.

@Matthew B Yes, this. I expected a bit more to be said about the utterly unacceptable and completely indefensible racist black centaurs. They’re absolutely horrible.

@MByerly LOL, as soon as I read “1969” as when Fantasia was finally popular I thought, “Well, DRUGS obviously.”

When I first saw this as a kid I like the Pastoral scene because I loved horses, mythology and centaurs, plus I liked the symphony itself, but it’s a farrrrr from perfect piece! I also liked Night on Bald Mountain immensely. That was it though. A friend in high school got me to watch it again in anticipation of the 2000 vers. but I’m just really not that enamored with it. I prefer tigher story, I guess.

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice part fits into the Read-Watch series.

http://german.about.com/library/blgzauberl.htm

I watched this at an incredibly young age, before I could really appreciate the music or the technical animation stuff, and it was always the Mickey one and the one with the demon that held my attention the most. Haven’t watched this in 15 years or more… probably need to.

Also loved the Italian parody Allegro Non Troppo

My first several exposures to it were of individual pieces occasionally clipped into the hour-long Disney shows that used to play on Sunday nights in the eighties – Mickey’s piece, or the dancing mushrooms, or the hippo ballet, etc. Fantasia as a whole began to take on a sort of mythic aura. It was a thrill the first time I finally was able to watch it all the way through, finally piecing together a complete picture of something I’d only been shown glimpses of, and that thrill has stuck with me.

Speaking of Disney, any word on how they are solving the 2023 issue yet?

Horrible pedantry follows:

Mickey started off with big oval eyes with pupils in Plane Crazy (the first Mickey Mouse cartoon animated though not first released), and the whites of his eyes turn into the familiar white ‘mask’ round small black eyes halfway through The Galloping Gaucho (the second one animated).

Aside: The Philadelphia Orchestra sued Disney in the 90s for a cut of the profits from DVD sales. Although it was eventually settled out of court, I was on jury duty at the Philadelphia federal courthouse one of the days the case was being argued. I wasn’t called for that case (or any other), but I remember that when a group of potential jurors was summoned, a lawyer or two would usually come to the jury pool room, for whatever reason. Although we weren’t supposed to know what cases were being heard, when an entire troop of identical, sharply dressed, absolutely “lawyer-looking” people all showed up in the room together, we knew it must be Disney.

@@@@@ 8: AeronaGreenjoy

Your URL does not link to an existing page. A little help here?

@17: Sorry. Here’s the beginning of the article: http://www.cracked.com/article_15677_the-9-most-racist-disney-characters.html

I’m another HUGE fan of Fantasia. I love the Nutcracker segment, the Ave Maria and the dancing hippos, ostriches and crocodiles. But the Pastoral Symphony….from the opening with the wondrous flying horses, through the centaurs and then the two almost Norse gods at the end. By the time the Rainbow goddess appears, I’m in tears. then Mother Night/Nut cloaks the earth in darkness and Diana/Athene shoots her bow… It’s perfection. Gorgeous.

@2/Lisamarie – Deems Taylor’s voice rocked. I had an LP that was my mother’s of him narrating Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra (why hasn’t Disney ever animated that? Or have they?) and The Nutcracker Suite (unrelated to Fantasia this time) that I used to listen to over and over as a kid, not just for the great music, but for that great voice.

When this and Lady and the Tramp were released at the same time at some point in the 80s, I for some reason vehemently argued for going to see Lady and the Tramp. I am unsure why – I think it’s because I liked the Siamese Cat song so much as a kid (being oblivious to its cringe-worthy reliance on ethnic stereotypes). My sister wanted Fantasia. For whatever reason, I prevailed (maybe because I was the oldest?), and to this day I’ve still never seen the complete movie. Not sure I want to, either, but I love the Sorcerer’s Apprentice bit and the Bald Mountain sequence, and thoroughly enjoyed your entire review, Mari (as I always do!)

I remember seeing the Chernabog in person during the closing parade at Walt Disney World.

I have a Christmas ornament that is a gold plated medallion of Mickey the Sorceror’s Apprentice

I loved this movie. I too remember seeing it in bits and pieces as part of Disney’s Wonderful World of Color. I’m pretty sure I missed the 1969 release. I did catch it in the theaters the next time it came around. I know I loved the Pastoral piece and the Dance of the Hours, Night on Bald Mountain and Ave Maria. I think I liked all of the pieces they chose. It left me with a lifelong long of the Pastoral Suite. I’ll have to give it another go on Netflix.

My late father used to tell the tale of how, when in North Africa during the Second World War (in a tank regiment) he and his buddies were given a 24 hour pass and hit Cairo on a little R&R. They went on a bender and crawled into a cinema to sleep off the alcohol, coming round groggily to Pink Elephants on Parade. They thought they had the DTs. My dad wasn’t a drinking man by the time I knew him. Perhaps Fantasia had something to do with that.

@23 – Pink Elephants on Parade is part of Dumbo, though :)

Nice paintings around…

With regard to the “Rite of Spring” sequence, I once met a geologist who told me that that sequence is a fascinating depiction of the “state of the science” of geology in the pre-“plate tectonics” theory era.

I remember reading that at the time of the 1969 re-release, one of the veteran Disney animators was on the college lecture circuit. He was asked once what kind of drugs they were on when they were making FANTASIA. He replied, “Ex-Lax and Pepto-Bismol.”